On Sask-E, however, technology has made possible an entirely new definition of personhood. Animals, robots, hybrids, and even doors and worms are in communication with the humans of the future. And thanks to a galactic accord known as the Great Bargain, they all have a valid seat at the negotiating table. Once the assumption that only humans are people is swept away, thorny questions of natural resource allocation, representative government, inclusive language and sexual freedom are up for reevaluation. (If you’ve ever wanted to know how a sentient train can couple with a robot or a cat, your answer is here. As one character remarks, “Where there’s desire, there’s data.”)

As messy as all this sounds, it opens up thrilling new pathways of hope that Earth 2.0 might succeed. The Terraformers, refreshingly, is the opposite of the dystopian, we’re-all-doomed chiller that’s become so common in climate fiction. Newitz’s mordant sense of humor steers the story clear of starry-eyed optimism, but it’s easy to imagine future generations studying this novel as a primer for how to embrace solutions to the challenges we all face. If we’re ever going to save ourselves from ourselves, then maybe what we need is a new way of thinking about self. —Siobhan Adcock.

Siobhan Adcock is a writer and editor whose most recent novel is The Completionist.

Nonfiction

Blood Money

A cinematic tour of ambition, greed and desperation in biotech

For Blood and Money: Billionaires, Biotech, and the Quest for a Blockbuster Drug

by Nathan Vardi

W. W. Norton, 2023 ($30)

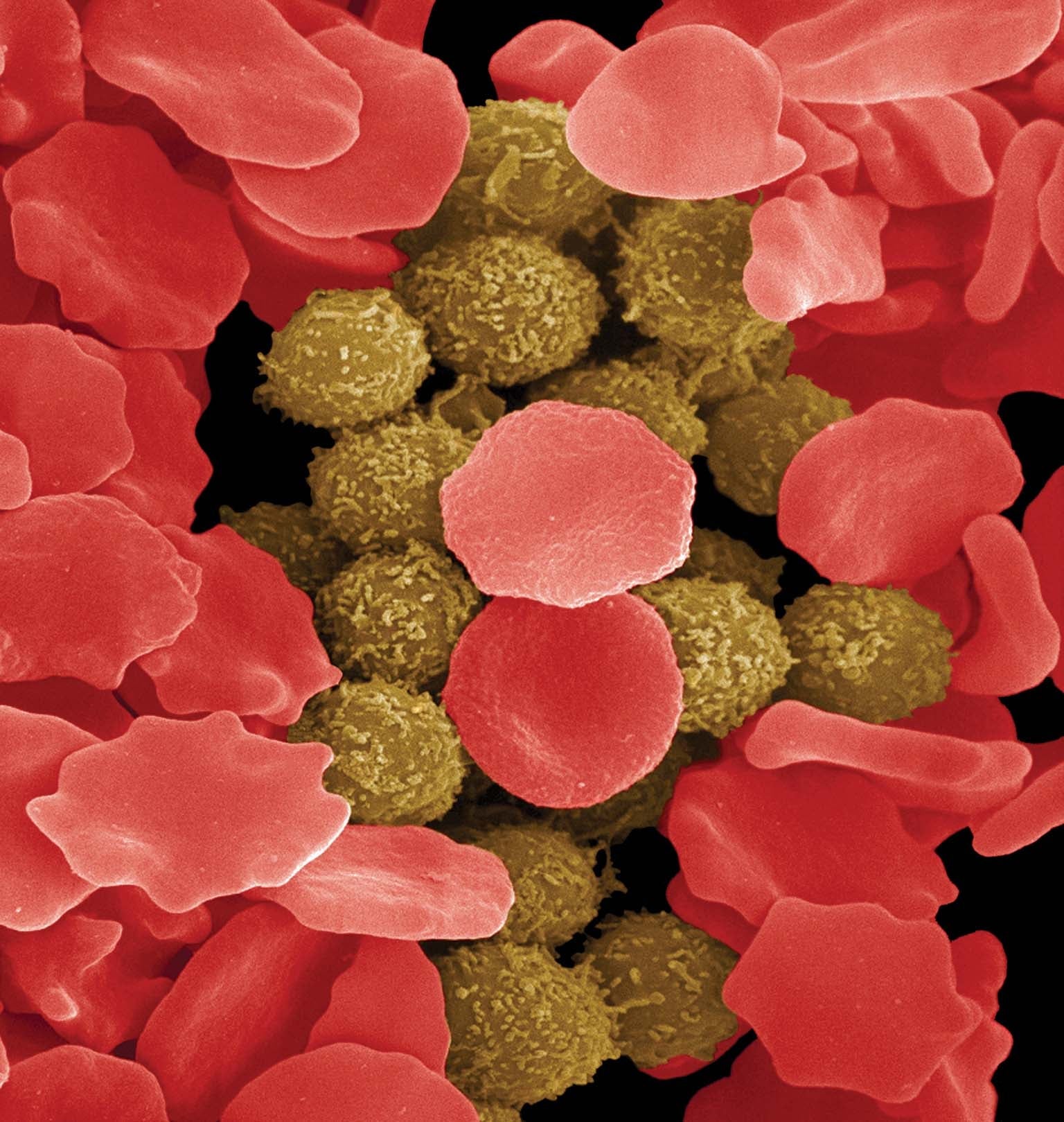

“Finding new therapies that target only cancer cells and did not kill healthy cells had become the holy grail of cancer drug development,” writes Nathan Vardi, a managing editor at MarketWatch and former editor at Forbes. For Blood and Money follows the path of one class of such products (“targeted small-molecule drugs” designed to fight blood cancers) that ultimately pits two biotech companies against each other in a race to market—and to an unimaginable payday. Readers are introduced to scientologists, restless entrepreneurs, clinical experts and the machinations of magnate financiers searching for the next billion-dollar blockbuster. In the middle of that friction of ambition and greed are the patients, desperate for cures and more time.

The story begins with Pharmacyclics, a small biotech company in California that is working on a drug to treat leukemia. Along the way, we meet charismatic and sometimes capricious executives and investors, as well as revolving doors of employees being hired, fired and starting new companies (and competitors).

Vardi examines the fraught, infamously slow FDA market-approval process, but the pacing of the book remains quick. With the focus on characters shifting from chapter to chapter and a vast number of names—people, companies, drugs—included for detail, it can feel at times that one needs a color-coded organizational chart to keep up.

In the quest for magic-bullet biopharma drugs, a particularly disquieting element is how powerful investors become drivers of medical strategy. The scientific search for cures often seems overmatched by the outsized desire to be first and to reap the highest returns; one could be forgiven for wanting to rename the book For Money and Blood. The profits are astronomical, yet investors still consider how much they’ve left “on the table.”

Still, there are meaningful collaborations, and many characters in the book genuinely want to do right for patients with deadly diseases. Readers remain distinctly aware of those who have benefited (and continue to benefit) from these drugs. Yet the banks, investors and hedge funds leading the search underscore an overall health-care system that feels skewed in its priorities.

Vardi, who is clearly knowledgeable about Wall Street and biopharma, depicts the nuances of both in a vivid, cinematic fashion. One can already imagine the movie version. —Mandana Chaffa

In Brief

The Land Beneath the Ice: The Pioneering Years of Radar Exploration in Antarctica

by David J. Drewry

Princeton University Press, 2023 ($39.95)

Glaciologist David J. Drewry takes readers to the frigid research outposts where he and his colleagues pioneered the technique of radio-echo sounding to plumb the depths of the Antarctic ice sheet. Drewry explains how this new technology emerged to compensate for inadequacies of past methods, then shares his own experiences mapping invisible mountain ranges and, worryingly, lakes deep under the ice that are hastening melt. A peppering of photographs and delightful personal anecdotes show the excitement and frustration that are inevitable during scientific expeditions. —Fionna M. D. Samuels

The Deluge

by Stephen Markley

Simon & Schuster, 2023 ($27.99)

Stephen Markley’s epic novel creates a full-scale panorama of a world bludgeoned by climate change, even as it magnifies the struggles of those caught in its vast and unrelenting chaos. Activist groups A Fierce Blue Fire and 6Degrees both attempt to provoke government and industry into addressing the climate crisis, but their divergent philosophies take them down different paths as society unravels. Markley’s dark depiction of the near future is filled with vivid descriptions of climate catastrophes, but his intricate network of complex characters balances precision with pathos, offering a kaleidoscopic view of humanity’s fraught relationship with its changing planet. —Dana Dunham

The One: How an Ancient Idea Holds the Future of Physics

by Heinrich Päs

Basic Books, 2023 ($32)

Which is more fundamental, the many or the one? Author Heinrich Päs believes physics gestures at an underlying unity simple enough to count on one finger. If only physics would embrace monism, its deepest mysteries would yield to that magic number. But monism was declared a heresy, first by the medieval Church and second, in Päs’s telling, by physicist Niels Bohr. Even if the connections between ancient monism and modern science are a stretch and Bohr is reduced to caricature, the history is thoroughly researched, the physics is cutting edge and Päs’s larger point resonates: much, or maybe all, of what we take for reality is an artifact of our limited perspectives. —Amanda Gefter

This article was originally published with the title “Reviews” in Scientific American 328, 1, 58 (January 2023)

doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0123-58