The risks associated with a bone marrow transplant used to treat HIV mean the procedure is unlikely to be widely used in its current form

In 2019, researchers revealed that the same procedure seemed to have cured the London patient, Adam Castillejo. And, in 2022, scientists announced that they thought a New York patient who had remained HIV-free for 14 months might also be cured, although researchers cautioned that it was too early to be certain.

Ravindra Gupta, a microbiologist at the University of Cambridge, UK, who led the team that treated Castillejo, says the latest study “cements the fact that CCR5 is the most tractable target for achieving a cure right now”.

Low virus levels

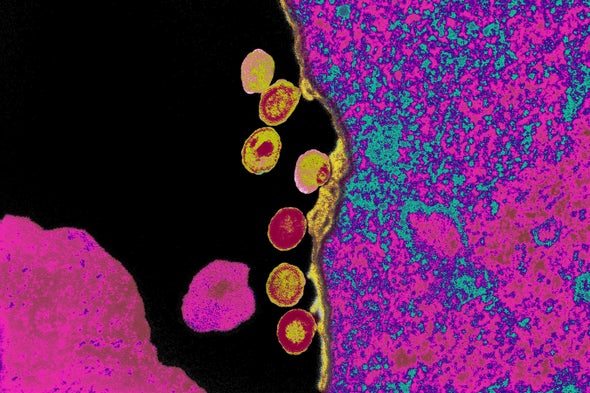

The Düsseldorf patient had extremely low levels of HIV, thanks to ART, when he was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukaemia. In 2013, a team led by virologist Björn-Erik Jensen at Düsseldorf University Hospital in Germany destroyed the patient’s cancerous bone marrow cells and replaced them with stem cells from a donor with the CCR5Δ32/Δ32 mutation.

Over the next five years, Jensen’s team took tissue and blood samples from the patient. In the years after the transplant, the scientists continued to find immune cells that specifically reacted to HIV, which suggested that a reservoir remained somewhere in the man’s body. It’s not clear, Jensen says, whether these immune cells had targeted active virus particles or a “graveyard” of viral remnants. They also found HIV DNA and RNA in the patient’s body, but these never seemed to replicate.

In an effort to understand more about how the transplant worked, the team ran further tests, which included transplanting the patient’s immune cells into mice engineered to have human-like immune systems. The virus failed to replicate in the mice, suggesting that it was nonfunctional. The final test was for the patient to stop taking ART. “It shows it’s not impossible — it’s just very difficult — to remove HIV from the body,” Jensen says.

The patient who received the treatment said in a statement that the bone marrow transplant had been a “very rocky road”, adding that he planned to devote some of his life to supporting research fundraising.

Timothy Henrich, an infectious-disease researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, says the study is very thorough. That several patients have been successfully treated with a combination of ART and HIV-resistant donor cells makes the chances of achieving an HIV cure in these individuals very high.

Gupta agrees, although he adds that in some cases the virus mutates inside a person and finds other ways to enter their cells. It’s also unclear, he says, whether the chemotherapy that the people received for their cancer before their bone marrow transplants might have helped to eliminate HIV by preventing infected cells from dividing.

But it’s unlikely that bone marrow replacement will be rolled out to people who don’t have leukaemia, because of the high risk associated with the procedure, particularly the chance that an individual will reject a donor’s marrow. Several teams are testing the potential to use stem cells taken from a person’s own body and then genetically modified to have the CCR5Δ32/Δ32 mutation, which would eliminate the need for donor cells.

Jensen says that his team has performed transplants for several other people affected by both HIV and cancer, using stem cells from donors with a CCR5Δ32/Δ32 mutation, but that it is too early to say whether those individuals are virus-free. His team plans to study whether, if a person has a larger reservoir of HIV at the time of receiving a transplant, this affects how well the immune system recovers and eliminates any remaining viruses from the body.

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on February 21 2023.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Sara Reardon is a freelance journalist based in Bozeman, Mont. She is a former staff reporter at Nature, New Scientist and Science and has a master’s degree in molecular biology.