Juan José stands on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande river, his brown eyes fixed on the long, snaking line just across the water. There, about 200 people wait for entry into the United States, part of a recent influx of asylum seekers headed for the border city of El Paso, Texas.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!But the 19-year-old Venezuelan is not among them. For the three days since his arrival, Juan José has been biding his time, waiting to see if a controversial US border policy known as Title 42 will end.

A rarely used section of the US Code dating back to 1944, Title 42 allows the federal government to turn away asylum seekers on the grounds of public health. Former President Donald Trump first invoked the law in March 2020, as the US grappled with the early days of the coronavirus pandemic.

But in the years since, Title 42 has been used to expel millions of asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border, prompting an outcry that it violates their right to due process.

In November, a US District Court judge declared the policy “arbitrary and capricious”, ruling to end Title 42. But the US Supreme Court on Monday has intervened to temporarily block the proposed expiration date, set for December 21. The decision comes in response to a petition from Republican officials in 19 states, who warned of a spike in asylum seekers if Title 42 expired.

The uncertainty over Title 42 has left individuals like Juan José in limbo, unsure of their future. And cities like El Paso continue to brace for an increase in border crossings, with El Paso Mayor Oscar Leeser declaring a state of emergency on Saturday.

As a bitter wind whips his rugged jacket, Juan José stuffs his shaking hands into his pockets and tells his story. It has been exactly two months since he left his home for the US; he did not tell his parents about his plans until he was already in Colombia.

His father was “surprised and sad”, Juan José said, but he understood his son’s desire to earn money to care for his brothers. Besides, what could his father do about it, anyway? “I was already on my journey.”

As he crossed from Colombia heading north to Panama, Juan José passed through the dense, treacherous forests of the Darién Gap. There, he saw dead bodies — other refugees and migrants, he assumed, who died “trying to get out of that f***ing jungle”.

Then, as he reached Mexico, he learned the bad news: Venezuelans, previously exempted from Title 42, now faced expulsion as well, as part of an agreement between Mexico and the Biden administration.

The agreement allowed a limited number of Venezuelans to apply for asylum in the US, but only if they could afford a passport and flight and had a sponsor in the US to help support them financially. Those arriving at the border would have to stay in Mexico.

“I got mad because [of] all the journey that I just went through for nothing,” he said. “But I kept going until I arrived to Ciudad Juárez”, a Mexican city across the border from El Paso.

Now, Juan José is weighing his options. If Title 42 ends, he may be bound for New York City. If the policy continues, either through Supreme Court action or as part of a congressional deal, the 19-year-old will settle in Mexico.

Thousands of people share Juan José’s predicament. The policy’s possible expiration has given hope to asylum seekers headed for the US. However, those hopes are tinged with uncertainty due to ongoing legal and political fights over the fate of Title 42.

Experts like Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, a lawyer and policy director for the American Immigration Council, warn that Title 42 exacerbates existing confusion around US immigration policies.

“Title 42 is a distraction,” Reichlin-Melnick said. The policy “is basically a blunt instrument for a problem that needs complex solutions”.

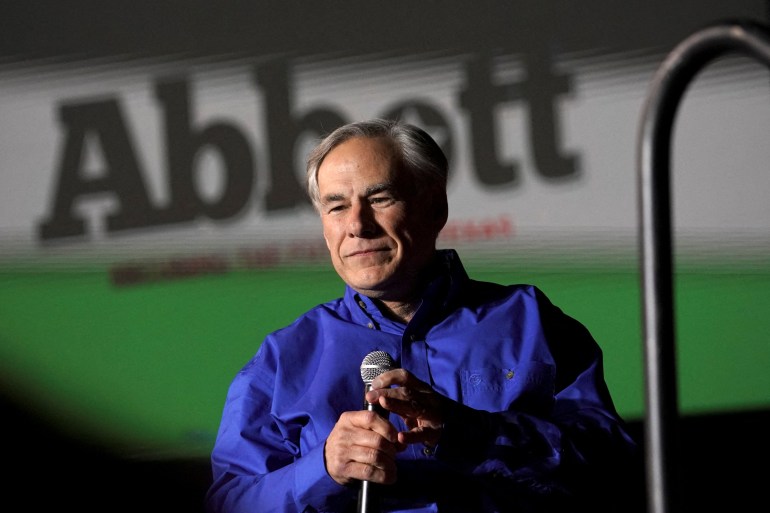

Politicians in Texas disagree. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton and Governor Greg Abbott want Title 42 to continue, and their state is part of the ongoing, Republican-led legal effort to keep the policy in place, for fear that a rise in border crossings could overwhelm government resources.

A federal appeals court on Friday declined to block Title 42’s end, opening the door for the Supreme Court’s decision to intervene on Monday. Reichlin-Melnick has called the Supreme Court the most likely path for Title 42’s long-term continuation.

Other politicians, like Texas Republican John Cornyn and West Virginia Democrat Joe Manchin, have previously petitioned US President Joe Biden to find a way to extend Title 42 past its scheduled expiration.

In a letter to the president, the two senators joined US Representatives Henry Cuellar and Tony Gonzales, both Texans, in pushing for an extension, claiming the US Department of Homeland Security (DHS) does not have “sufficient support or resources” to manage the end of Title 42.

DHS has issued an outline of its post-Title 42 plans (PDF), though details are scant. It focuses largely on revisions to the asylum system, as well as a proposal to send more resources like medical supplies to the border.

“The only real solution,” the document states, “is for Congress to fix our broken and outdated immigration system.”

The Biden administration, meanwhile, has signalled it wants Title 42 to expire, though the White House is said to be considering a policy that would cut the number of refugees and migrants eligible for asylum from countries like Venezuela, Haiti, Nicaragua and Cuba.

Such a policy would be an extension of the agreement limiting Venezuelan asylum seekers. It has drawn criticism for being similar to a plan put forth by former presidential adviser Stephen Miller, an immigration hardliner who worked for the Trump administration.

In a statement released on December 13, Homeland Security secretary Alejandro Mayorkas sought to downplay any changes to US border policy should Title 42 expire.

“Once the Title 42 order is no longer in place, DHS will process individuals encountered at the border without proper travel documents using its longstanding Title 8 authorities,” Mayorkas said.

“Let me be clear,” he continued. “Title 42 or not, those unable to establish a legal basis to remain in the United States will be removed.”

Under Title 42, some asylum seekers were sent back to their home countries, but most were simply taken back to Mexico, making it easier for them to try crossing the border again. According to US Border Patrol data, repeat apprehensions grew by roughly 20 percent after the use of Title 42 began.

But if the policy does indeed expire, experts like Reichlin-Melnick predict people attempting multiple crossings will face harsher punishment, including the possibility of federal deportation, a more formal removal process that carries significant legal risk. For instance, people who attempt reentry after a formal deportation may be arrested and imprisoned.

“There’s no doubt more people will be released [into the United States] in the short term,” Reichlin-Melnick said of Title 42’s expiration. “The real question is the long term. There will be more people being charged for misdemeanor illegal entry, more deportations and, ultimately, fewer crossings.”

He likens Title 42 to “putting a band-aid over a festering wound”.

Robert Painter, legal director of the refugee rights organisation American Gateways, said the US immigration system is ill-equipped to handle modern drivers of displacement such as climate change, domestic violence and non-state actors like gangs and cartels.

He is currently preparing to litigate an asylum case involving a woman from Honduras who fled to the US after suffering domestic violence. Women like her may seek asylum because there is no hope for protection or legal recourse in their native countries.

“It’s required hours of time, hours of testimony prep and 350 pages of evidence, and I still couldn’t say this [case] has a good chance for success,” Painter said.

Meanwhile, there is rising tension between his organisation and Texas politicians like Paxton, who is currently investigating American Gateways and other nongovernmental organisations for purportedly using money from the Texas Bar Foundation to “support the border invasion”.

Border cities have already started to see a surge in crossings, with El Paso noting a jump beginning in late August. Advocates and city officials told Al Jazeera that shelters are already brimming with too many people.

“Everything is extremely fluid, so to tell you exactly what our plan is, it’s a little tricky because it’s so fluid,” said Laura Cruz, a spokeswoman for El Paso.

Cruz noted that the city recently spent $9m to house, care for, and relocate refugees and migrants from Texas to destinations like Chicago and New York City, though the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may reimburse the city for most or all of that money.

Back on the banks of the Rio Grande, just outside of El Paso, Juan José dreams of landing in New York City. So do other asylum seekers nearby. Josefina, a 21-year-old from Venezuela, hopes to make enough money there to pay for better heart medication for her father. Brothers Brian, 8, and Miguel, 11, also plan on life in the big city.

While their mother goes to find water, the siblings sell cigarettes to people waiting in line.

“They say us Venezuelans are the worst,” Miguel said. “That’s why we are not allowed to enter the US now — only people from other countries. We crossed over a week ago, but were immediately turned back to Mexico.”

Now, like Juan José, they wait.

“We want to go to New York or Miami,” Miguel continued. “They say it’s beautiful, but I don’t know. Is it too far from here?”