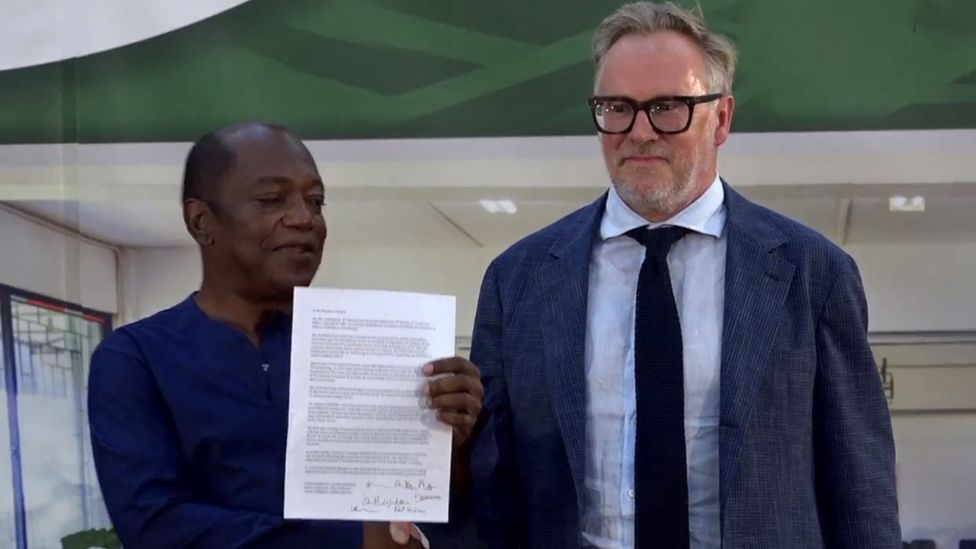

Charlie Gladstone read an apology to the people of Guyana on behalf of his family

The descendants of former Prime Minister William Gladstone are facing calls to pay reparations to Jamaica for an ancestor’s role in slavery.

The Gladstone family apologised for its slaveholding past in Guyana and pledged to fund research into slavery and other projects at a ceremony on Friday.

But the family has been accused of failing to acknowledge the case for paying slavery reparations in Jamaica.

The family told the BBC: “At the moment we are solely focused on Guyana.”

“There is a huge amount to do here [in Guyana],” the Gladstones said.

John Gladstone – the father of William Gladstone, one of the UK’s most revered prime ministers – was one of the largest slave owners in the British West Indies.

The University of London’s (UCL) Legacies of British Slavery database shows John Gladstone owned or held mortgages over 2,508 enslaved Africans in Guyana and Jamaica in the 19th Century.

He was paid more than £100,000 in compensation after the British Parliament passed a law to abolish slavery in most British colonies in 1833, receiving £15,052 for 806 enslaved people in Jamaica.

Reading the family’s apology to Guyana, Charlie Gladstone, the great-great-grandson of William Gladstone, condemned slavery as “a crime against humanity” and acknowledged “slavery’s continuing impact on the daily lives of many”.

He said the family supported a 10-point reparations plan proposed by Caribbean nations.

But there was no mention of John Gladstone’s slave ownership in Jamaica at the ceremony in Guyana on Friday, nor in the family’s statement announcing their intention to apologise and make donations last week.

John Gladstone owned “significant properties” in Jamaica, said Verene Shepherd, director of the Centre for Reparation Research at the University of the West Indies.

She said the Gladstone family “must come to the scene of the crime and apologise to the people who live in those neighbourhoods”.

The Jamaican academic and professor of social history urged the Gladstone family to “commit to reparations, as they’re doing in Guyana”.

Reparations are broadly recognised as compensation given for something that was deemed wrong or unfair, and can take many forms.

Last week, the Gladstones said they would aim to donate £100,000 to the University of Guyana’s International Institute for Migration and Diaspora Studies, which was launched on Friday.

In Guyana, the family also pledged funding “to assist various projects in Guyana” and UCL’s Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slavery for five years.

Prof Shepherd said: “Now that we realise that we’ve been ignored, I think Jamaica should make an approach.”

The BBC has been told that Jamaica’s National Council on Reparations is discussing the Gladstone case and considering what action to take.

The council has not had any contact with the Gladstone family to date.

Reparations approach

John Gladstone was a Scottish merchant who made a fortune from his ownership of sugar plantations and enslaved workers in the decade before abolition.

His prominent involvement in the industry shaped the political career and legacy of his son, William Gladstone, whose attitude towards slavery changed over his life.

In his first speech to Parliament, the Liberal prime minister defended the rights of plantation owners, but later branded slavery the “foulest crime” in history.

Image source, Hulton Archive/Getty Images

William Gladstone was Liberal prime minister on four occasions in the 19th Century

The Gladstones are the latest British descendants of slave owners to attempt to atone for the actions of their ancestors in recent years.

The family’s historic link to slavery came into sharper focus during the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020.

Since then, some members of the family have joined the Heirs of Slavery, a group of British people whose families profited from the transatlantic slave trade and want to make amends.

Other members include former BBC journalist Laura Trevelyan and her family, who apologised to Grenada and promised £100,000 in reparations in February this year.

In an interview with the BBC earlier this week, United Nations Judge Patrick Robinson said he had “some scepticism about these families”.

He said the reparations paid should be based on the number of slaves John Gladstone owned and the extent to which the family benefited from this economically.

He said he would be willing to ask for a calculation from the Brattle Group, an economic consulting firm that produced a report on the reparations states owe for their involvement in slavery.

“If it’s not to be seen as a tokenistic exercise, if it is to be taken seriously, they must ascertain the reparations that are owed,” Mr Robinson said.

The Brattle Group Report, which was co-authored by Mr Robinson, said the UK should pay $24tn (£18.8tn) for its slavery involvement in 14 countries.

The Gladstones should undertake a similar calculation to “demonstrate how much is really owed”, said Robert Beckford, professor of climate and social justice at the University of Winchester.

The professor said that rather than giving money to a university for further research, he would have “preferred them to talk to community organisers or reparations groups, to explore what is the best way forward”.

Although he welcomed the Gladstone apology in Guyana, he said the failure to acknowledge Jamaica hinted at “an unwillingness to face up to the full brutal, bestial horror of chattel slavery” in the country.