When Egyptian artist Ramy Essam describes Metgharabiin (Outsiders), his new album, released on Friday, he talks of rage, nostalgia, longing and sorrow.

Thank you for reading this post, don't forget to subscribe!It chronicles a life in exile laced with bouts of loneliness and hope. And in light of everything that Essam has been through over the past few years, it marks a departure from his earlier work.

“Through the years, my music was always centred around standard rock music mixed with Egyptian culture – Egyptian music culture and North African music culture,” Essam explained to Al Jazeera.

“But this album is very unique and different. It has a very stand-alone sound, [unlike] anything I’ve done.”

The work was a product of COVID-19 when Essam lost his ability to tour and was locked at home for a considerable amount of time, forced to reckon and reconcile with his own experience living in exile since 2014.

He contributed to the production of one of his albums for the first time and worked remotely with Stockholm-based producer Johan Carlberg. Neither consciously intended to create the album’s distinct electronic sound.

Instead, it manifested organically as Essam was toying around with his music production software, sampling tunes and creating demos that birthed a fusion of his statement traditional rock composition and the powerful, industrial electronic music heard throughout all of the 12 featured songs.

His creative juices flowing, Essam found that the most challenging part of finishing the album was choosing which songs from his rich repertoire would make the cut.

“I have maybe like 20 more songs or so in the same direction [of this current album] because this has been my life for nine years,” he told Al Jazeera laughing.

Metgharabiin (Outsiders), according to Essam, is not only political and revolutionary but also tells his story and that of several people whose fate has been similarly tainted by exile.

In January 2018, Essam’s Egyptian passport was revoked by the government, leaving him in paperless limbo, unable to travel. It’s an event that has since shaped his art.

Leaving the homeland

By the middle of 2013, Essam was almost completely restricted from being able to perform in Egypt, and his music was largely censored from state-controlled media outlets.

While his guitar was not physically stripped away from him and his powerful voice could still rile up Cairo’s Tahrir Square, the revolution was taking a stark turn from its eruption in January 2011 and instead went through a coup, bringing about military rule.

At this point, journalists, activists, artists and civilians calling for the ouster of the government were being targeted, arrested and thrown in jail. Essam didn’t escape the beatings or the arrests, but he eventually made it out of Egypt in 2014 after he was offered a two-year artist residency in the Swedish city of Malmo.

His song Irhal was for a long time the anthem of the 2011 revolution, which overthrew President Hosni Mubarak – a song that inspired millions of people swelling Tahrir Square to sing along to the lyrics in unison.

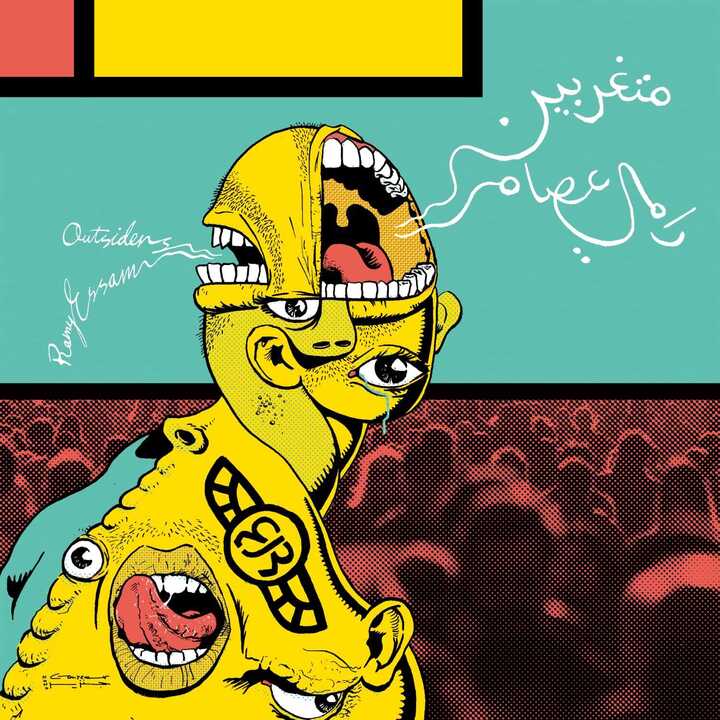

In keeping with this theme of exile, Essam tapped Ganzeer (a pseudonym, meaning “chain”), the prolific Egyptian street artist, to work on the cover art for this album. Known for his murals of protesters who perished during the Tahrir Square uprising, Ganzeer was forced to flee Egypt in the aftermath of the revolution after his art angered the regime.

Prominent poets and soulful tracks

The album doesn’t fail to make powerful statements, especially the tracks El Amiis El Karooh (The Flannel Shirt) and Lagl Tentesri (For You to Win), written from behind bars by the activists Galal el-Behairy and Ahmed Douma, respectively.

“Lagl Tentesri (For You to Win) is so powerful. It’s Ahmed Douma’s experience of being in jail for eight years,” Essam said.

Douma was arrested in 2013 in relation to demonstrations against the criminalisation of public protests. He was first sentenced to three years in prison, but during his time in detention, he was charged in a second investigation into 2011 protests held at the cabinet headquarters, and his sentence was increased.

The song was penned on the 10th anniversary of the revolution, and Essam said, “You can see his pain and anger in that we still didn’t win the fight” even after all the sacrifices that he and fellow Egyptians made.

Simultaneously, it describes hopefulness and the need to “still carry on the fight, and not just in terms of revolution, but it reflects on anything in our daily lives”.

The pain, loss and sadness of being away from your people and loved ones is elucidated in El Amiis El Karooh by el-Behairy, an Egyptian poet, lyricist and activist who has been in detention in Tora Prison in Cairo since March 2018 on a wide range of charges, including “terrorist” affiliation, dissemination of false news, abuse of social media networks, blasphemy, contempt of religion and insulting the military.

The title track, though, is wholly Essam’s own creation.

“Metgharabiin, I remember exactly how I wrote this track,” Essam said, with a wistful smile, twirling his long curls.

“The idea of the song started to develop between 2013 and 2014, but then I wrote it in the last week I was in Egypt,” he said.

“I wrote it because at that time I was banned. I was banned from performing. My music was banned from everywhere [in Egypt]. The revolution was struggling so much, and it was the first time we couldn’t protest, we couldn’t go out to the streets. We lost the square, and everyone was blaming the revolution [for the country’s failures].”

Written between Egypt and Sweden, the first few lines of Metgharabiin speaks of “strangers in our lands/years come and go/the world is against us” and describes the feeling of being an outsider in Essam’s own homeland. The rest of the lyrics were completed in Sweden, where Essam also found that he was an outsider. His album, he said, is fundamentally for those who feel the same way.

“If somebody wants to live Ramy Essam’s experience of being an outsider, you can listen to this album,” he said. “I want everyone that is feeling like an outsider not to feel alone, that we are together, and to find unity and to find peace.”

Disrupting dictatorship

Commenting on the oppressive rules of censorship in Egypt, Essam believes art has the power to disrupt any dictatorship, hence the regime’s fear of artists and their creations.

“It’s a force that they fear because they have zero control over it. As soon as a song is released and another person hears the song, they can carry it and pass it to the next one. It’s over [for the government],” he elaborated.

Essam said he has been a victim of cyberattacks after the release of some heavily politicised and anti-regime songs. His reach and streaming numbers also declined, and it seemed that interest in his music had dropped.

But it appears as though his music is being shared, just through more clandestine methods.

“In the last couple of years, you kind of feel helpless about [the numbers] because you’re fighting against the regime with all their cyberarmies,” Essam said. “[But] I found out that people in Egypt, … they share [my music] between each other through WhatsApp, through Telegram, because it’s not that safe for people to share it publicly.”

‘No regrets’

Despite the exile, the loneliness and everything else that accompanies it, Essam said his motivation is quite simple. “The only thing that matters is the documentation of the era in a form of political art,” he said, explaining that he hopes this art will defy attempts by the powerful to write their own narrative.

The importance of the responsibility to produce this art, to act as the archivist for one’s time, is something he hopes to impress on the next generation, which he believes is on track to succeed where he could not.

However, he admitted that the struggle is ongoing, and that since the revolution, things in Egypt have deteriorated. “Everything is much worse,” he said, “and that’s why many people curse the revolution and curse the generation that made the revolution.”

But change always comes at a cost.

“I am here now because of one single decision of me going out to join the Egyptian revolution,” Essam said, reflecting on the difficulties of the past decade.

“It was also a journey that was full of beauty and moments of freedom I’ve never felt before. If I go back to [that moment] a million times, I will go out to the streets again. That will never take away from the hardships and struggles, but no, no regrets.”